“The opinion- that has prevailed in some places, that the interests of the Southern States differ from the Northern, with regard to Manufactures, is evidently erroneous.”

- The Constitutional Whig, 1828.

February 22nd, 1844. In the House of Representatives:

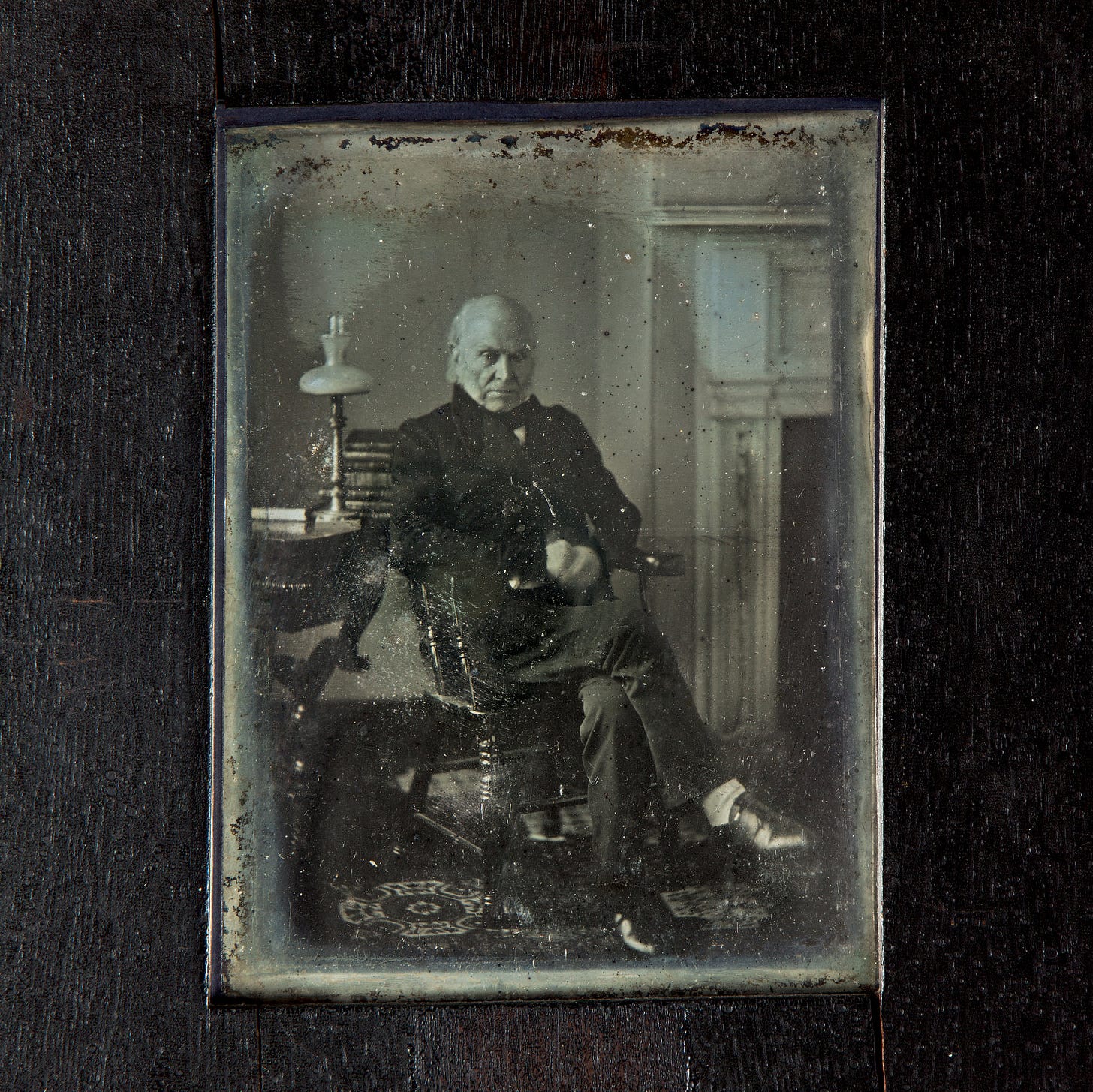

Mr. Dellet closed with Mr. Adams, quoting from him some remarks in favor of the abolition of slavery, concluding with a prayer, that in “God’s good time, it would come, and let it come.”

Mr. Dellet asked Mr. Adams if he understood him.

Mr. A. nodded assent, and said with great earnestness, let it come

[…]

The remark of Mr. A. here excited considerable sensation in the House, and Mr. Dellet proceeded. I am, said he, one of the few who in 1824 believed that it was better to have a Civilian elected to the highest office in the gift of the people than a military Chieftain. It was then I voted for the gentleman from Massachusetts. I cannot ask my country to forgive me for this offence, but I do ask pardon of my God for it.

James Dellet, the sole Whig congressman from Alabama, was not alone in being one of many southern men to support John Quincy Adams for president. The Massachusetts firebrand was not perceived as the abolitionist he really was in 1824 and 1828, leading to many southerners supporting Adams for the presidency. In Louisiana, Adams had received 46.99% of the vote in 1828, making it his best-performing southern state, even ahead of Kentucky. What compelled these Southerners to support the son of the Sedition Act? The answer is both simple and complex.

For all intents and purposes, southerners who voted for John Quincy Adams often did it for the same reason northerners did. Men like James Dellet often supported John Quincy Adams for aristocratic reasons, denouncing Andrew Jackson as a "military chieftain." Others were worried about the halting of internal improvement programmes or the lowering of tariffs. However, what is particularly interesting is that although the reasoning is the same, the reasoning behind the reasoning differed, and I have divided supporters for Adams in the South into two categories: the western supporters of Adams, and the aristocratic supporters of Adams.

By "western supporters of Adams," I do not just mean the supporters of Adams in western southern states like Missouri, Kentucky, Arkansas, etc., but also the westerners within deep southern states like Alabama, Mississippi, and Virginia.

By "aristocratic supporters of Adams," I refer both to large planters, who generally opposed Adams in fear of the "military chieftain," and also to those who supported the growth of manufacturing businesses within southern states and tariffs.

The western supporters of John Quincy Adams were primarily concerned with internal improvements and how this would develop the American frontier in each state. The connection of the west to the whole of a union would allow it to develop in the nationalistic vision of Henry Clay. The Weekly Natchez Courier, a far-western Mississippi paper, reports:

The people of the North and West would be benefited, in having raw and good roads, through their country […] What has retarded the growth of Natchez? nothing but the want of good roads into the interior of the state.

Or the Anti-Jackson Convention of Missouri which noted that Thomas Jefferson

approved two nets for making a road from the frontier of Georgia to New Orleans, without requiring the consent of any state […] the principles upon which these acts were passed have, ever since, been maintained, to the manifest advantage of the Union.

The concerns of these western areas were clearly serious, as in the western parts of Alabama and Mississippi, Adams enjoyed a larger number of supporters than the rest of the state. A pattern that continues into modern-day West Virginia.

This pattern, however, clearly differs from where most of Adams' support lies. Adams performed particularly poorly on the frontier of North Carolina and better on the east coasts of Louisiana, North Carolina, and Virginia. In all cases, the primary cause of these results seems to be the more "aristocratic" supporters of John Quincy Adams. Some richer cotton or tobacco planters, but especially sugar planters, as The Ariel notes, in publishing an address "to the citizens of Louisiana":

[I]f the duty is taken off sugar and molasses, would not the capital now employed in their production be directed to the culture of cotton, much to the injury of those who are now engaged in this agriculture? And yet, all these measures are in contemplation, and warmly advocated by the friends of Gen. Jackson

The lowering of tariffs could be dangerous to west Mississippian and Louisiana sugar planters, and their interest would be directed more towards Adams. As well, in the South, a simple acceptance of northern industrialization was coming from planters who believed the nation was benefiting from diverse production. Even James Madison admitted by 1833, "our country must be a manufacturing as well as an agricultural one, without waiting for a crowded population." Especially so in Virginia, the dream of an agrarian republic was losing its grip. As Richmond’s pro-Adams paper would write,

The natural consequence of Manufactures, is, to enhance the value of agricultural produce in every part of the country. […] It is said, in some memorials on this subject, that a manufacturing village or town has only an effect on its agriculture in its immediate vicinity; time has shown that the effect is general […] products of agriculture are delivered from ports in Virginia or North Carolina, at a cheaper freight, at the door of the manufacturer, than the price of twenty-five miles land carriage

Both aristocrats and westerners saw the benefit of Henry Clay’s American System, and connecting the nation through ideological and material nationalism was beneficial to all sections, no matter how different they may have been.

In the end, although men like James Dellet survived into the 1840s, and even Dellet supported nationalistic principles like tariffs and the national bank, the Nullification Crisis and increasing tensions over slavery drove out most of the country's Adams-voting nationalists. Men like John C. Calhoun and John A. Quitman, who switched from internal improvement supporters to states' rights supporters, leaving behind nationalism in the South for the path to secession.

Southern men who voted for John Quincy Adams did not differ as much from northern men who voted for John Quincy Adams; just as northern frontiersmen and monied aristocrats existed, so too did the South have frontiersmen and sugar aristocrats. In the end, the southern men who voted for Adams represent a time when the country was more united and southerners could more easily vote for northerners; even those who did not abandon their principles of internal improvements and a national bank, such as James Dellet, came to regret voting for the Massachusetts firebrand. With this view in mind, we can see how the South’s strong rejection of internal improvements later in time came to represent a rejection of the North as an economic entity.